A thin strip of sand-edged road, fast eroding, separates the Vineyard Sound from a large salt pond the Wapanoaug named Sengekontacket, place where the brook flows. Here, the cormorants scritch scritch from the opposite bank, and a flock of blue-white gulls rear up in a wild, undulating fracas, but the water is still and temperate, good for swimming and getting the hang of a boogie board, for physically accepting that the only way to stay on the thing for more than a bucking moment is to lay on it with your legs straight and dead and your chest pressing up, like a sphinx. Brady supervises this process while I help Ottelie look for shells: the beginnings of oysters, with their potato chip translucence, cockles, slipper snails like speckled big toes, arcs, with their radial groves, bow-tied, slate gray scallops, periwinkles. I palm a near-perfect specimen of the last, my daughter being out for quantity and size over gnomonic perfection. “A baby,” she sing-songs, over every find small enough to fit in her own palm.

The shell of a winkle, like other mollusks, grows with a beautifully progressive geometry: at any given angle from the tiny seed at its center, the width between each successive spiral is the width of its precedent raised to same exponent. The exact size of this exponent varies from winkle to winkle, which is why some look more like a nautilus, and others, like a whelk.

Sam Kriss on the town of Hastings’ Winkle Club: “The rules of the club state that every member has to carry a winkle in their pocket at all times. One member can, at any point, challenge another to ‘winkle up,’ at which point they have to take out their winkle.”

Or what, I wonder? Disbarment?

Days later, I will find the perfect periwinkle in the pocket of my shorts, and and I will make the mistake of telling Ottelie to winkle up. “My shellie,” she will say, in a tone that brooks no argument, and remand it.

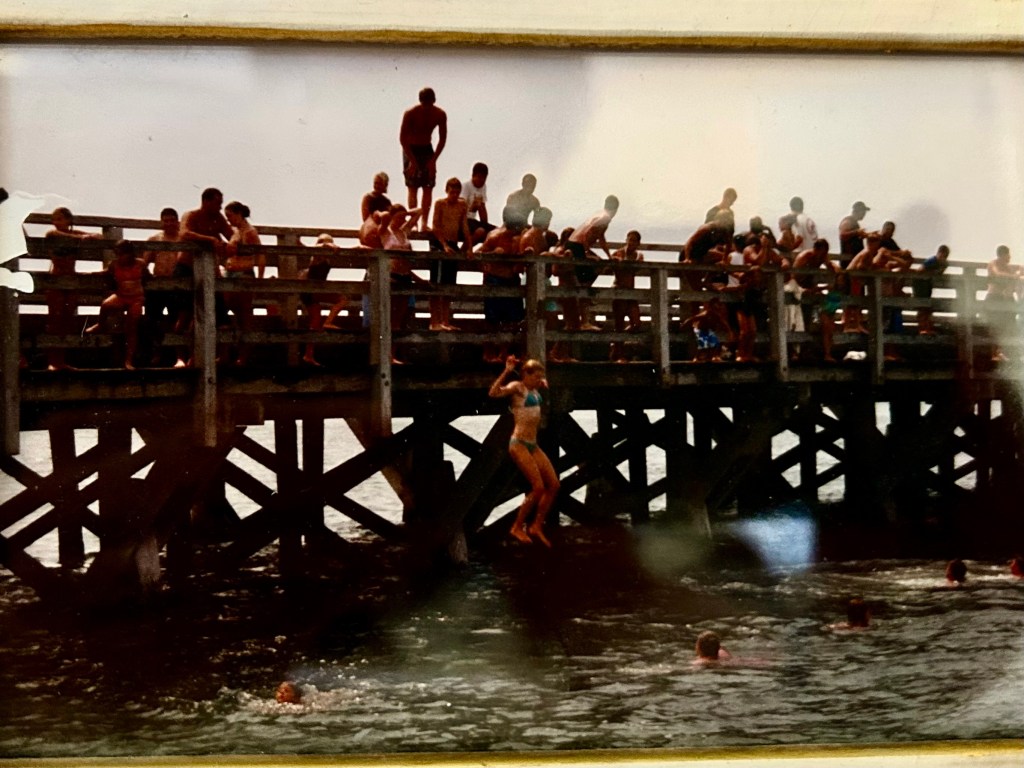

Up at the point, the occasional motorboat chortles and easy does it steers between the narrow joists of the low-lying bridge, underneath the waiting, ruthless eyes of the children who’ve gathered to watch the teenagers jump.

I was fifteen the last time I scrambled up on the ramparts and jumped; fifteen in a teal string bikini borrowed from my mother that I did not and would never fill; in the picture, I am a long white streak of rib and leg midway between the wood and the water; the white abruptly broken up by teal. That was the year my friend A and I were dying to ride mopeds, but my father refused to lie about our age to the old man who rented them out. (That was okay, because what we were really dying to do was to ride on the back of cute boys’ mopeds, our arms threaded around their waists, while the wind whipped our hair, just like Mary Kate and Ashley in that movie where they went to Rome.)

Here, I feel carefully with my toes for the sharp edges of an oyster or the rounded huckle of a clam. Though the shoreline’s narrow band of sand extends partway into the salt pond, the least movement disinters the silt underneath, which billows up in near-black plumes. The minnows are attracted to these plumes, for some reason, as is Irving, who watches from atop his red board while I validate with my eyes what my toes have dredged up. “What is it? What did you find?”

Four times out of five, I’ve found a rock, with clammish or oysterly attributes. Irving thinks one out of five is a sporting ratio. “You’re so good at this, Mom,” he exclaims. The clams, cherrystones mostly, and the more denuded of the oysters, go into a beach pail half full of water until it’s time to leave. The boys are not pleased with the call to toss them back, but with no shucking knife and a good twenty minutes between us and the house, what else are we going to do?

Here I dug for clams alongside my paternal grandfather. He would fill his plastic floating bucket in the blink of an eye, the tines of his clam rake clinking almost rhythmically, while I felt around with my fingers and swaddled each concentric circle of shells in ungainly layers of seaweed. Back at his house, the shells would be plunked onto sheet pans full of crushed ice – the ice there to relax the clams, fool them into louvering their shells a few millimeters, at which point they were ready for shucking. My grandfather could shuck a dozen cherrystones a minute, faster than my siblings and I could get them down, which was pretty fast (even the ones dusted with cigarette ash).

Unclear when and where my grandfather developed the taste for quahogs. Not in Pearl Harbour, where, at not quite twelve, he and the other members of his boy scout troop rowed their dingies into the harbor to rescue sailors. Not at Stanford, where he was nearly thrown out for coaxing a herd of nearby cows up to the second floor of Encino Hall. Perhaps he had geoduck while he was living in Seattle, after he’d dropped out of Stanford (he’d meant to go to Anchorage), and figured a reduction in size would surely improve the design of this animal. It could have been in Korea, whose baekhap comes close, in heft and brine, to the quahog. Surely, it could not have been Atlanta, where he, a young United Press International photographer, first encountered my grandmother, then a reporter. My grandmother, a born deep Southerner fiercely set on heading north, (sharp-elbowed under that scrim of delta gentility), never warmed to shellfish.

My grandfather was a newsman all his working life, a writer turned photographer who made the push towards audio back when live reporting was, incredibly, the dominion of print, and the radio for bulletins and commentary. Blather and sugarthroats, my grandfather called them. My grandfather, who avoided dulcet tones as he would later avoid cleaning services and physicians, thought an outfit with as deep a bench of reporters as UPI ought to be able to leverage their talents on the airwaves just as well as on paper, hang the tricky accents and far-flung static.

All I recall talking to him about as far as his life in news went were the adventure stories, like the time he’d disguised himself as an athlete during the Israeli hostage crisis, or the time he hid in a trunk in the Georgia statehouse in order to hear the young governor Talmedge decry the Brown vs Board of Education decision.

Here, at a desk that looks out onto Menemsha Pond, I find an oral history he’d given to an old coworker about his time getting UPI’s audio business off the ground. (As it turned out, his bet on audio news had been a smart one. UPI’s radio business would, by the early seventies, be the nation’s largest, with close to two thousand stations.) The piece is colorful, familiar, exacting on the principles of story. ”Story telling is story telling and whether you do it with images or words or sound, it is still story telling. Editing with a razor blade is no different than editing with a pencil or shaded light. (Gombrich’s “Art & Illusion” still the bible for all three.)” he wrote.

I read and re-read the essay and wish there were more of it, more of him. I settle for adding a hardcover copy of Art & Illusion to my Amazon cart.

He’d retired and moved to the Vineyard the year after I was born, though in my child mind, it seemed like he and the little house he’d had built had always been there. The apotheois of bachelor retirement. It was essentially one open room, this house, with a small bedroom off to one side, and a lofted sleeping area reached, thrillingly, by a heavy, unanchored oak ladder. The walls were prematurely yellowed from all the cigarette smoke and choked with stacks of books – waterlogged paperback editions of every Pulitzer winner and New York Times best seller of the past half century, interspersed with the occasional, destabilizing Harry Truman biography. My uncle’s large, slumping sculptures lingered in unexpected places, like beside the toilet and underneath the sink.

His kitchen was perpetually in shambles; his khakis were sun-bleached and frayed, and the madras shirts he favored under his suspenders had been washed and line-dried so many times they were all the muted periwinkles and violets of the quahog’s interior. He had an outdoor shower, big, long-past weathered, crunchy with lichen, and if you were lucky, you might find a half a sliver of Dial soap wedged between two of the slats.

In addition to clamming, he was a dedicated deep waterman, and he cooked with uncommon attention to flavor. He was the first person I knew to salt a cantaloupe, to grill bluefish in loose tinfoil and tilt the drippings into a bowl to be shoved and not forgotten in the fridge for next week’s chowder.

Like me, he could not smell (he on account of the cigarettes; me, on account unknown). If he considered this a handicap, he never said, but the afternoon he came home from fishing to find my father had replaced his refrigerator was one of the few times I can remember him genuinely angry. We’d maybe been on the island half a day at that point, most of it spent taking the old fridge to the dump and then going to Crane Appliance up in Vineyard Haven to get a new one. I remember thinking my grandfather would probably be happy to have a brand new fridge, maybe even grateful to my father for dealing with all the boring and malodorous logistics. Instead, he came in with his wheelie cooler full of striper and blew his lid at the temerity of it all: losing a perfectly good fridge was bad enough, but losing the contents was unstomachable. What about the monkfish frames he’d been keeping for stock? (Gone.) The cheese my uncle had brought down from Syracuse? (Definitely gone). What about the leftover spaghetti water he’d been saving to sauce the fish we were about to eat that very night. My father hadn’t thrown out the spaghetti water, had he? (Here, my father must have hoped that his father was pulling his leg. Who saved the water left over from boiling pasta? That wasn’t depression-era frugality; that was nuts. But he wasn’t, and it isn’t.)

(The only time I can every recall him angry with me was when I threw away the pack of cigarettes I found in the side pocket of his old truck. The self-righteousness of a nine year-old! )

For my fifth Christmas, he got me my own clam rake. The rake had a good foot and a half on me, along with six, talon-like steel tines, and was confiscated as soon as my grandfather departed. He would pass away, of leukemia, before I grew tall enough to use it.

The summer after he died, my father and his three siblings held a memorial at his house. It was supposed to be a party, though my father choked up at the end of his eulogy – not unusual considering the occasion, and also not something I’ve witnessed before or since. It was supposed to be a party, and so I wore a party dress, tie-dyed silk, with spaghetti straps. “Inappropriate,” someone – my grandmother? – said, not so sotto voce, of my dress. There was a raw bar, with a hired shucker, since my grandfather wasn’t around to do it. My younger brother and I ate so many clams we had to be shooed away.

Here at twelve, I would tear through someone’s left behind copy of Summer Sisters, read it over and over in the dusty seclusion of the half finished room over my grandfather’s garage. That was the year that there were so many of us kids relative to the size of my grandfather’s house that four of us slept in tents in the small backyard. I hated my tent, which I shared with my sister: the air was over-baked and frowsy and there was no privacy. There were six kids when there had been four, and I was in the middle, when I’d always been the oldest; in the middle, I couldn’t just demand to be left alone and expect to be listened to. Along with the little beach past the marina, the garage was a refuge.

Summer Sisters wasn’t the first book I’d read with sex scenes in it – there’d been that romance book club my friends and I had taken up towards the end of fifth grade, and a few passages in Lady Chatterly’s Lover, and the all-white copy of The Story of O that I was forever removing and then reshelving, just so, from my mother’s windowseat bookshelf. But Caitlin and Vix had started more or less where I was – twelve, awkward, yearning to move past childhood – and within three summers, they had done it.

I had a boyfriend that summer, but I wasn’t sure we were even together. I liked the idea of having a boyfriend, I liked telling the girls I went to camp with about him, in the most general sense. But he was about a foot shorter than I was and his lips were wide and stretched like saran wrap across the loom of his mouth. Bru and Von, the boys Vix and Caitlin got together with – they had their own cars, and there was no way Vix or Caitlin had to crouch down to kiss.

I could have taken Summer Sisters home with me; whomever it had once belonged to was not about to come looking for it. But I didn’t; I reshelved it just like I’d reshelved Story of O, only I had to wait a whole two years before I could re-read it.

The next summer, my father rented a house in Chilmark instead of staying at my grandfather’s. The house overlooked a salt marsh and the August light was often golden, rippling, the blueberries growing so abundantly that even my industrious brothers could barely make a dent. That was the summer my cousins from Taiwan came with us, and the summer Lady Marmalade, to my father’s great horror, was resolutely unavoidable, and the summer I looked in the mirror at myself in my white Nike tanktop and was genuinely surprised to find that my silhouette did not look at all like Kirsten Dunst’s in Bring It On, and not only because I had no boobs.

Here at Lucy Vinson beach, in Chilmark, my children drift towards the piebald clay cliffs, rust and pumice and peach where the light hits just right. You cannot climb the cliffs – this is apparent just by looking at them; just by looking at them, you might cause a small, dusty avalanche. Yet I had come away with crude clay birds shaped from stolen handfuls of these cliffs; the birds nested in the third row cup holders of the suburban that just barely held seven children and two adults; they nested and slowly disintegrated over the next two years.

The surf at this beach hucks small and medium-sized stones at your ankles at the break. The break is a sharp one, the waves furious. My older son does not get cold – rather, he puts aside how cold he gets for the delight of being pummeled by these waves. My younger son is warier, and more interested in digging for treasure, in the form of the little grey sandcrabs that make their homes in tunnels at the swash.

Here the boys spring easily, swiftly along the granite boulders of the Lobsterville jetty until they are within hook distance of the fishermen who surf cast for bonito and albacore. Ottelie and I trail; she is insistent on crossing the treacherous maws between the boulders herself, accepting only the occasional hand. When at last we reach the jetty’s end, the boys are chatting excitedly with the fishermen. One points to a spot maybe twenty yards beyond, where the water buckles. Dolphins.

Just last night, Perry whispered, not for the first time, but with a first time’s gusto, that he loved being on the Vineyard. What did you love most, I asked.

Well, one of the best things was being a dolphin, he said (only I thought he said seeing). Catherine takes me out deeper than you do, he added.

What was the other best thing?”

“Clams.” (Which we’d eaten, this time, out of the raw bar window at Larsen’s, in Menemsha.)

As I was closing the door, he piped up:

“But mom? Mom –”

“Shhh.”

“Next summer, you have to bring the shucking knife to the shell beach.”

I say we will. Brady will shuck them.

“Good,” he says. “I’m not throwing back any more clams.”

Leave a comment