I come home from New York ravenous. Nine forty five at night, that backlit dark of mid autumn, with it tremulous hunter’s moon. I hear soft music and O’s high, piping voice – she is in her bed, curled against my mother, looking at photographs of herself.

Only when she is very tired will she lay her head in the crook of my neck with any sort of permanence. At a quarter past three, she is relentlessly aware of the people and objects in the room, of what they might offer. When I snuggle in beside her on a cold Saturday morning, she opens my eyelids, fingers my necklace, issues requests for fresh water, a napkin, a recount of the many lovies that guard the left upper corner of her bed. She wants breakfast; she wants peppermint tea. And the brothers: are they up? And Daddy?

I relieve my mother and hold O for a little while, standing, enjoying the stillness of her. I sing the abbreviated version of the bedtime song my husband has made up for her; I turn off the lamp and, noticing the light bleeding from the boys’ closed door, go in and unplug the string of christmas lights.

Downstairs, I wolf the rest of a beef stew I’d made before leaving, along with a half quart of brussel sprouts. I have not had an appetite for weeks, and now I am eating cold beef, still slugged in gelatin, and enjoying the quiet of the night kitchen. What was that cookbook of recipes for one? Alone in the kitchen with an eggplant?

Dinner, with small persons – as anyone knows, it can be a real slog. If we aren’t careful, the conversation will revolve around the dinner itself, and how much must be eaten to earn the eater a popsicle. This, to the incredulity of my husband, whose answer – all of it! – has never wavered.

Sunday, I bring the dictionary to the dinner table. Everyone gets a word. The children clamour for their words. The dictionary is nearly half as heavy as Ottie, half her height. With great effort, she turns to O-P. Her first word is peduncle. A single stalk ending in nerve fibers, or a solitary narcissus. Perry’s is dichlorophenoxyacetic acid. Weed killer, in other words. Irv’s is cantilever.

Each night, they add a word. Dreggy. Refugee. Refraction. Speculum. Driftage. Petrify. Zodiac leads to a good ten minutes on astrology. The basics of astrological signs is knowledge I’ve absorbed more than acquired. I am, nonetheless, the relative authority in our household, for my husband knows only his own sign (Leo). P is a Capricorn, which suits and pleases him no end. Irving is no Virgo (logical, systematic, perfectionist, all about inputs and processing? Then again, he is just past five, and will tidy the playroom if asked); Ottelie, born in Cancer’s ebb, seems more Leo. Though, again: what is three if not a lion?

When I began working in the entertainment division of Conde Nast, Susan Miller’s Horoscopes were the most popular video series we had. I recall purple and swirly, cumuloid pink title cards, at odds with the plain, blunt-bobbed astrologist. There was a woman who worked on our floor who adored Susan Miller; her desk was a minefield of tarot cards and astrological charts. She believed in the spirit world, and came, on occasion, to the office in fairy wings, or a velvet cape.

Autumn arrives early this year, with delirious intensity. Even I, in my blinkered, intermediated state, notice how brilliantly scarlet the sugar maples are, for last year they’d been dulled by months of damp. We’ve had hardly any rain since labor day. The few overcast days have hacked and hemmed like cats and like cats slipped away. For nearly a week in September, the moon is a low-hanging peach pink that softens the treelines in the darkening sky, furring their branches.

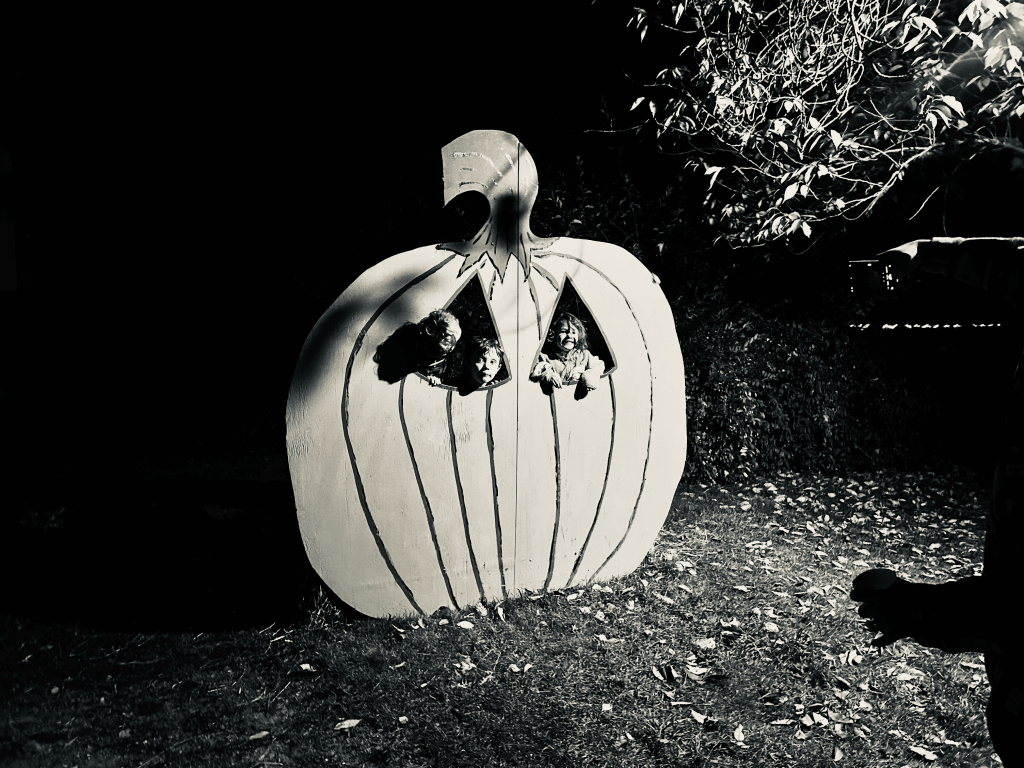

There is one day towards the end of September where for some reason it is just Ottelie and I and we go to walk and scooter around Wellesley College. She rockets down too-steep hills on her scooter, and makes light, clattering work of the boardwalk. On her own, she is not forever rushing to catch up. I listen as she houses her school friends in the campuses many towers. To Maddie goes the cathedral; to Teddy, the windowless smokestack. How will you visit him? A ladder. And for Halloween, they’d all come out. And who lives in the cathedral? And who lives in the tower? And when was Halloween? Ottelie’s stories have a circular shape, a techno pitter patter. She has to get one rotation in before you get how it clicks.

Why you like to read stories mom?

(For i am always reading at the edge of her bed while she plays with her cadre of lovies, or puts the sibley’s book of birds cards back into P’s old wallet.)

Tell me why?

? ? ?

WHY?

P is eager to write. He spells independently, guessing when he is unsure. His stories are event-driven summaries; the events are lifted from his own life or from shows or films. I try to explain and then to draw a story arc. Rising action, falling action. But he likes a continuous rise, an upping of stakes right up until he runs out of paper, so my expected mountain is just a series of crook and staffs. Why does the panda punch the old granny in the face, I ask, but get nowhere.

Irving, though: that child understands story. He likes a little surrealism (finding an orca, say, at the town lake), understated drama (getting bitten by the orca), and a quick, unceremonious resolution (catching the orca and going home). But this understanding is instinctive, with no need of clumsy diagrams.

Just before the bus comes one recent morning P and I are hastily assembling a collage of “small moments.” The time I went to the beach. The time I got my ribbons. The time dad let us go into the basement.

The bus is about to come, and so I manage not to say that those are not sentences, but fragments. Perry, looking as I scribble, notices I’ve changed some of the captions.

Mom. He’s indignant. I told you what to write. Why are you changing it.

I defend my second-rate sentences. I’m adding action! Surely he will appreciate that.

He scowls, takes the poster. A sentence starts with a capital and ends with a period, he says.

Capital. Period. THIS IS A SENTENCE, PERRY. this is not

P brings home a book about Titanic from the school library and we pour over the diagrams of the ship’s cross-section, the many stratified compartments, the meticulously thought-out layer cake of class and mechanics. In the book, chance plays a larger role than it does in the movie. In the movie, the ship’s fate, introduced within minutes, is for the next hour underscored by the constant and voluble hubris of its architects, the exuberant guilelessness of the passengers. In the book, you learn about the many icebergs that strafe a thousand miles of Atlantic sea, including those the ships ahead of the Titanic were dangerously close to hitting that same night. So deluged with iceberg warnings was the titanic’s radio operator that the one about the iceberg they would ultimately hit went unread. One of the ship’s lookouts spotted the iceberg with his own eyes, and by then it was far too late. Turning a ship that large is a matter of minutes.

One of the more incredible parts of the Titanic’s story is that it was foretold almost exactly, down to the ship’s name, size, watertight compartments, and paucity of lifeboats, fourteen years earlier.

It is P who notices the gaps in the watertight compartments. Shouldn’t the bulkheads go all the way up? The book does not say. It seems so easy, so obvious outside of extra bedroom conversions, to leave no gap. On the other hand, they are billed as “watertight.” I ponder this; we look at the point of shearing; the bow pulling down, down as the stern tilted up. I picture a little tinfoil boat, like the ones I sometimes make out of a sheet of printer paper. I pour water into the little boat and it pools evenly. But if the water cannot pool evenly …

I do not explain this childlike visualization to P. You’re onto something, I say. (Though, having visualized my little boat, now snapping in two from the weight of the trapped water in its bow, I am having trouble working out the point of compartments at all).

P’s teacher tells me he learns differently, like a black box. He loves large numbers, infinity in particular, and subtracts and adds with ease, but gets frustrated by his illegible handwriting. He sounds out each individual letter in most words, but has a professorial vocabulary. How peculiar, he says, when Irving’s dinosaur goes missing. He has taught himself to “finger knit,” in his own words, and produces bracelets and ropes of a uniform intricacy. He is captivated by the original bathysphere, and the Trieste, the bathyscape successor. We look at black and white photographs of both. One is a sphere, and the other, a blimp, with a cylindrical submersible. Bathys – the ocean – is the joinder; mechanically, the bathysphere and the bathyscape have little in common.

For weeks, he’s been working on a blueprint for a robot. The robot starts off fanciful – it will climb trees and spy on bad guys and find treasure – and becomes a sort of uber butler, as they are wont to do.

I stare at the blueprint, which is, already, schematically detailed. How would it actually work, though?

Most of the programming I do is static. I rarely need to write my own functions, because some other, far more competent programmer, has already written them. Robotics seems more like web development: a lot of contingent commands. If this, then that. If motion, then light, or sound. If tree, then drive beak forward. If beak in wood, wrap arms around tree. Fine. The if/then, I understand. But how does a robot know motion from stillness, solid from nothingness?

I recall an extraordinary profile I’d read years ago, on a blind man, Daniel Kish, who learned to see the way bats do, using echolocation. He clicks and taps and the way the sound carries tells him about his surroundings; whether there is an object ahead of him, whether it is moving, how large it is. The pictures he is able to produce are richly detailed, like sonar scapes, bereft only of color. A sensor operates on a similar principal to echolocation. It is not actually seeing or hearing or feeling; what it is doing is observing change, or difference. (One of these waves is not like the other.) The change is the signal.

In order to make him dinner and clean his room, P’s robot will need sensors.

P is not, in the beginning, particularly keen on understanding how his robot will do the things he wants it to. I should leave it be – stop crimping his imagination! Certainly, I am ill-equipped to explain eletrical engineering, or circuitry, or hardware. But: robots aren’t magic. Childrens’ books so often explain their subjects’ magnitude or distance in feet, or pounds, or light years – as if a young child has any concept of 10,000 feet. Better to show the brachiosaurus beside three school buses stacked vertically. Proportions, as Archimedes knew: these are easily understood.

It clicks, anyways, without my pushing it too hard. Soon enough he is asking about motion versus light, and what’s a capacitive sensor again? Like a bathtub that knows when someone gets into it?

That’s right, I say. And manage not to start on about volumetrics or buoyancy.

A friend mulls having another child. How could there be enough time?

Time is finite. You divide it into three, instead of two. (As if it is so linear.) (As if I know anything!)

The thought of spending less time with her two makes her sad, she says.

I recall the hours we’d spent in her kids’ playroom one Saturday morning this summer, allowing ourselves to be filigreed in tiny plastic gemstones, speaking in soft-shoe, gentle voices and slipping easily between our own continuous and small persons’ discrete conversations.

Later, we were on the back patio, in that soporific Washington heat – or it was soporific for me. I drank my beer and admired the trellis of squash, the many tomatoes quickly reddening in their tubs. My friend was up and down the steps of the patio, in and out of the enclosure, helping the children go safely down the slide, monitoring the water level in the inflatable pool.

I did not sense imminent danger in these objects – and the reason I did not was not because these were not my own children. My husband is the one who senses danger, who installed the safety gates and panicked over worn away patches of paint, who makes sure the children apply sunscreen and insists on age-appropriate car seats. I am my father, picking me up from swim practice with an open can of Busch Lite in the open bracket of the Saab cup holder – not because he needed it (the one would be his only; he was as likely to leave it, still half full, in the car when he returned, than to finish it), but because why not?

Likewise, I go in our own playroom less than any room in the house. When it is empty, I will, on occasion, lie on the couch. When it is not, and I do go into it, it is to request that one or two of the small persons walk on my back, a mutually satisfying activity.

I’m very selfish, I text.

A selfish person, golem-like with her time, and disinclined towards all but the narrowest, most tractable manifestations of anxiety (seasonal activities, broken machines) can say something airy and blithe about time being finite and what has already been allotted to children being what is reallocated, versus taking from what has not, and have that be, once the hurdy-gurdy of infancy is past, be more or less true.

Another truth: I am no longer a mother to very young children. I felt this to be true nearly two years earlier, when Ottelie was perambulating, steady on her tiny feet. It will, of course, only become more true, not less. This – circuitry and storytelling and pouring one’s own cereal, cutting apples for the salad with a paring knife and losing no fingers, cutting, in fact, fairly neatly – is progress.

(Though, three is nothing like almost seven. Three thinks she is almost seven, but also wants to be carried around. Three believes herself to be everyone’s main character, while seven knows that we are all our own main characters. (Unclear what zany five, that imp, thinks.))

So why the ache? Because I myself have not changed? Have, if anything, regressed?

Because I love babies, and struggle to shut a door that hasn’t yet shut on its own?

After Ottelie, we deliberately gave away all baby accouterments. The crib, the infant carseat, the bouncer, the high chair with its treacherously angled legs. The many soft and sturdy receptacles for babies: all gone.

I do not want a mini van, or a suburban. We have not yet flown with all three children at once. We do not even have a regular babysitter who is not a family member.

We have only seven more months of two daycare payments; we have only a year and seven months (but who’s counting) until all children are in public school.

If I have another baby, I will move backwards and forwards simultaneously, and thus achieve equilibrium. (I am not having another baby.)

I am frequently nauseous, with cold feet and colder fingers. For two months, my right wrist buzzes if not thoroughly wrapped. I need iron, I need B vitamins; I need to get out of my own head. Maybe I partway want another child because I enjoy the cycle of metamorphosis, the waxing and waning.

A directive I’ve soured on: take gentle care of yourself. Have we not been gentle enough?

Also: the over-proliferation of “cozy.” We do not need to be so cozy and comfortable all the time.

Why have I switched to “we?”

Sometimes in my dreams, I am walking along an old carriage road now entirely covered in grass. Beeches and ash and oak trees are thick on one side, scrubbier pines on the other. In my dreams, I am pushing a stroller, walking a dog. There are others, with me; the dog or stroller is the prow and then me, pushing, being pulled, and then the others, veeing in either direction. It is late autumn or early spring; the grass is still or newly green; the sunlight weak, sliding along the thickets.

In the four years we’ve been back in my home town, I’ve driven by the old house weekly. The new owners have put in juniper hedges around the outer fields, and, closer to the house, a sturdy plank fence. If I slow down, passing by, it is only slightly, enough to see that the pool is still there, with a much larger pool house, and that the doors and shutters are not sage green, instead of forest.

Next to the house was a private road where I learned to ride a bicycle (by being pushed, screaming, down the entry hill), and then, later, to roller blade, and where I made piles of green walnuts every fall, where my friend A and I hosted a highly successful, and extortionate, lemonade sale, and then a far less successful yard sale. The road, never ours to begin with, is more effusively private now. I am not always a rule follower, but have an abiding dread of being clocked for being somewhere I am not welcome. It is a road, and I could very well be driving down with the intention of visiting one of the residents – but the thought of being on the receiving end of a chilly “can I help you” keeps me away.

“Think of the kinds of experiences you have when you are not expected to be,” commands Sara Ahmed, but in general, I’d rather not.

So it comes as a surprise to find myself running down the private road of my own accord, one sunny day in mid October. I’d had a route all planned out, a precisely nine mile route into which the private road did not factor into this route, and yet there I am, turning left. I run by the old house from a newly fresh vantage point and notice, for the first time, the ambitious series of raised beds within the walls of an old tennis court. I run by the swamp, which has gone vermillion and carmine first, as swamps do here, and which bares no trace of the ancient refrigerator, lined with asbestos, that my mother unearthed in the course of getting the property ready for sale. And then, just past the old stone pump house, I veer right, onto a narrow, forested path. The sign at the edge of the path informs me that the path is private, and welcome to residents and neighbors. What counts as a neighbor? I do not want to explain myself. It has been eighteen years.

At the fork, I turn left. On one side is an outlet to the lake fringed in mist and ribboned scarlet, and on another, a hill angling steeply up to an enormous house, watchful and grey. I am prey under the gaze of the grey hilltop house, with its many, panoptical windows. I am a white woman, thirty six years old, in a $70 Tracksmith tank top; I know where I was going, and that I do not belong. , I dart across the open stretch. The forest cleaves in and then, quite unexpectedly, empties me out upon a grassy carriage road, blanked by scrub pines and deciduous trees; the tawny field of a nearby farm just visible.

I have not dreamed up anything, only added people.

Leave a comment